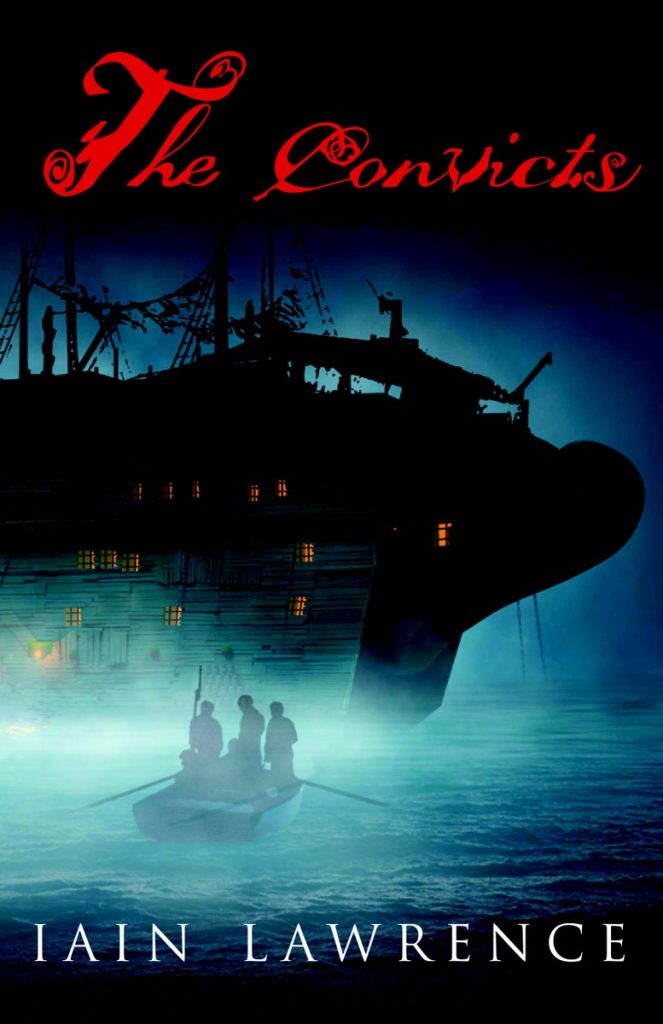

The Convicts

Buy the Book: Amazon, Barnes & Noble, IndieBound, Indigo

Buy the Book: Amazon, Barnes & Noble, IndieBound, Indigo Published by: Random House

Pages: 208

ISBN13: 978-0-440419327

Overview

After seeing his father hauled off to debtor’s prison, Tom Tin sets out to take revenge on Mr. Goodfellow, the man responsible for his family’s misfortunes. But the fog–filled London streets are teeming with sinister characters. Tom encounters a blind man who scavenges the riverbed for treasure—and wants what Tom digs up; Worms, a body snatcher who reveals a shocking surprise; and a nasty gang of young pickpockets who mistake Tom for someone ominously known as the Smasher. And ultimately, Tom comes up against the cruel hand of the law. Accused of murder, Tom is given a sevenâ€year sentence. He is to be transported to Van Diemen’s Land with other juvenile convicts. But Tom can’t abide life on the Hulk, the old ship where the boys are temporarily held. He decides to escape. But if he’s to succeed, his luck needs to turn…

Praise

“(The Convicts), aimed at those mature and strong-stomached enough to endure Tom’s horrors, powerfully draws readers into another time and place, and gripping Dickensian coincidences abound. The ending offers a glimmer of hope for down-trodden Tom and also leaves a door open for a sequel.” *Starred Review*

— Publishers Weekly

“To say that this lively novel is Dickensian is to understate its debt to that author. The story abounds in terrifying villains, grime, misery, and cruelty…This book is as action packed and as thoroughly researched as the author’s seafaring trilogy, but it will be accessible to a wider audience because of its easier reading level. Give it to reluctant readers who are looking for an exciting adventure.”

— School Library Journal

“Brilliant writing, adventure and a likable character mired in the claustrophobic dark of a 19th-century convict ship will entrance all readers who love an old-fashioned tale well told.”

— Kirkus Reviews

“[What] readers … will find unforgettable is the gritty historical fact, especially the horror of the young convicts’ daily struggle and the wretched suffering of 500 children packed and punished on the ship.”

— Booklist

Q&A

Q: You have left quite a few doors open at the end of The Convicts. Are you planning to write a sequel? If so, we were wondering if Tom’s seasickness would play a part in the next book. Does he eventually get over it, as well as his fear of the sea? Will Tom ever get his diamond?

A. The Convicts is the first book of a trilogy. Next is The Cannibals. Then The Castaways. (I think of them as my C stories.) Tom’s seasickness will lessen as he spends more time on the water, but he’ll never overcome it. (Admiral Nelson, the great hero of Midgely, was seasick at the beginning of every voyage.) I don’t know yet if he will conquer his fear of the sea, or if—instead—he will learn to be a master of his fears. But he will certainly come to understand his father’s love of the ocean.

As for the diamond, I’m not sure what will happen. I have two or three possible endings in mind for The Castaways. Tom might well discover that he just doesn’t want the diamond, that he has no need for its wealth.

Q. How did you develop Midgely as a character, and why did you choose him to be the supporting character? Why did you choose for his eye to be blinded? Why not choose some other horrific event? Why does Midgely seem so calm after he loses his eyesight? Why did you choose Penny to be the one responsible for Midgely’s blindness?

A. I wanted Midgely to be instantly appealing because I didn’t think he was going to be around very long. But I grew too fond of him to bring about the nasty end I had in mind, and instead gave him a deep knowledge of ships and sailing so that he could be Tom’s help and guide. Now I’m pretty sure that Midgely will stick with Tom right to the end.

He is blinded because that is a true story. On the real hulks, a group of boys blinded another, and that incident summed up for me the absolute horror that these ships must have been. The real boy was too scared to name those who’d attacked him, and so suffered his blindness much as Midgely does.

But Midge remains fairly calm because his life has been so hard. He’s the youngest boy on the ship, yet already he’s had his father desert him, and his mother cast him onto the streets, and he’s kept himself alive by sticking wires into dogs. It seemed right to me that a boy like that, too small to fight against anyone, would suffer through his blinding as he imagined that his heroes would—with a quiet courage. I liked the idea that Tom would be led by a blind boy. In the sequel, Tom and Midge try to find their way through the islands that Midgely knows only from his book.

Benjamin Penny was originally going to be a kind and gentle boy. His role was supposed to be the one that Midgely took on. I first imagined him as “Little Penny,” Tom’s closest friend. So, in a way, Midgely and Penny are really one character divided, much like Tom and the Smasher.

Q. Why did you feel compelled to begin the story with death? Was there a message or theme you were trying to get across by writing this book?

A. The beginning that you read in the finished book isn’t the first one that I wrote. But your question interests me, because my very first stab at the story also began with a death, though a different one. It began with the Smasher’s death, and the ringing of the passing bell. But I realized there were things that had to be said before that point in the story. I began with the death of Tom’s sister because that, to me, really shaped him into the person that he is at the start of the tale—a boy with a mad mother and a fear of water.

This question reminded me of a quotation about beginning and ending a tale with a death. But I couldn’t think of who said it, and couldn’t find it again. In this story, the death is not meant to carry a message.

Q. While writing this book, did you find yourself getting emotional and reacting to the story even though you were the one writing it? Did it make you feel sick to write about Midgely’s eye? Did you feel disgusted when you wrote about the moldy food? Did you feel depressed while writing such a sad story?

A. To answer this I have to explain how I write. I type the story on a computer keyboard, but as I’m typing, I’m telling the story to myself, speaking at times only half aloud, under my breath, and at other times loudly enough to be heard in the next room. So the story seems quite real to me. I’m hearing, and speaking, the words of the characters. I see in my mind what they see in their real, but fictional, lives. So, yes, there are parts of the story where I feel the same emotions as the character. But Midgely’s eye was different. I had to talk with a doctor to find out what would happen to an eye that had been punctured by a needle, and I wrote about it with a clinical mind. The moldy food did not disgust me, but the story did leave me depressed at times. I had some quite troubling dreams during the worst part of it.

Q. Why did you name Worms, Worms? What were the doctor and Worms going to do with the bodies? Was Worms helping Tom because Worms was kind or was he trying to use Tom?

A. I can’t say how I chose the name Worms. I remember that the name came later than the character, and that I then thought about changing the man to suit the new name. “Worms” seemed to suggest someone thin and oily, who would move as though slithering, while I’d imagined the grave robber as being rather big and hefty. He would have to be, really, to hoist corpses out of graves, so I left him as he was.

The doctor needs dead bodies for dissection. This is true to the time. There were people who made a living delivering bodies to the doctors—usually anatomists—who needed them. The way that Worms goes about lifting the Smasher’s body from the grave is how it was really done.

Worms is based on the description of a London scavenger of the time. In the 19th century, the city swarmed with a wonderful and bizarre assortment of people who combed the streets for things they could sell. They picked up the castaway butts of smoked cigars, and sifted through sweepings for bits of wool. They collected birds’ nests, and horse manure, and dog droppings, which were used for dressing the leather of gloves and book covers.

Q. The book groups were very interested in the character of Tom’s mother. What happens to her? Why was she the only woman in the book? Why did you write with such feeling about the mother grieving over her child’s death?

A. To be honest, I don’t know yet what happens to Mrs. Tin. The scenes of her grieving were meant to show her madness, and to make Tom seem a bit selfish for not sympathizing with her. She’s not exactly the only woman in the book—the Darkey is another, and there’s the fisherman’s wife who appears near the end—but it’s true that women are scarce in the story, and don’t come across very well. That, again, is a reflection of the hulks. Girls were not imprisoned with the boys.

Q. We’re a little unclear about how the Smasher died. Can you elaborate on that? What history does the Smasher have that makes others fear him so? Why do you refer to the Smasher as a twin throughout the whole novel?

A. It’s never really explained how the Smasher died, because Tom would have no way of knowing. As I imagined it, the Smasher lived a very violent life on the streets—as a thug and a thief until he was rescued in by a charitable group—there’s a passing comment about “the sisters” taking him in—and lived “on the parish,” or under the care of a parish church. The parish was a church jurisdiction, with officials that often included an overseer of the poor. The Smasher must have become quite useful or popular to have had the passing rung at his death.

He is as referred to as a twin because that is how Tom imagines him. To Tom, the Smasher is his twin in a physical way, his look-alike or “doppelganger.”

Q. Why was the grave robber your favorite character? Why did he need Tom to see Walker? Besides being instrumental in introducing Tom’s look-alike to the story, what is his overall importance in the novel?

A. I liked the grave robber best because he’s a quirky sort of character. I liked to imagine him outside the bounds of the story—where he would go at night, and what sort of friends he would have, and how he became what he was.

Worms will appear again in The Castaways. His importance will then be obvious.

I’m disappointed by the puzzlement caused by Worms and his “Walker!” He’s not referring to a person when he says that. Walker was just an expression that meant “Nonsense!” There was a particular way to pronounce it, stressing the second syllable. If someone was particularly unbelieving, he might say “Hookey Walker!” If you’ve seen the movie of A Christmas Carol, with Alistair Sims as Scrooge, you’ve heard the expression. When Scrooge, on Christmas morning, shouts down to a boy on the street to go and buy the big goose at the butcher’s shop, the boy shouts back, “Walker!” and starts to run away.

Q. What inspired you to write about this subject? What is the appeal of 19th century England? What kind of research did you do for this book? Did you intend the book to be for young adults? How long did it take you to write?

A. The inspiration for this story came from the true tales of the boy convicts. I thought, at first, I would write a story that would have far more truth than fiction—about the boys on the real hulk Euryalis, and the actual efforts of a kindly chaplain who did all he could to make their lives as bearable as possible. But I doubted if I could write that true story properly. There is a lot of information about the hulks that was never recorded, or is so hard to find that I would have needed years of research. Even for this version, where the hulk is almost like a background, the research was very difficult and time consuming. I have a friend who is a fabulous librarian, and she tracked down books and old newspapers, and transcripts of a government study. She sent her husband to a London museum to photocopy the actual plans of two real hulks.

I wrote the story in about four months, after a very long period of research and planning. Revisions took another few months, in various stages, so that I probably spent a good year with the book from the day I began writing until it was finished.

I like 19th century England as a setting for many reasons. I don’t feel at all familiar with modern children, so it’s easier to invent characters from a past that’s fairly distant but not really all that far away. My father, who is from Cambridge, is certainly not 19th century, but he saw the end of sailing ships. As a boy, he got his milk from a man on a horse-drawn cart, and kept his meat and milk in a “meat locker” outside. There were no refrigerators, and ice was too expensive.

I like a time when people used horses. I like a society divided into classes, and a city that includes everyone from a king to a bone grubber. And I love the terms that Englishmen invented, such the “beer engine” that was really just a pump to lift beer to a bar from the barrels in the basement.

Q. Do you relate to a particular character? Have you been involved in or seen conflicts that relate to the conflicts in the novel? Are any of the experiences that Tom goes through extracted from your life? If so, which ones?

A. Not one of the characters is based on a real person, and only one thing that happens to Tom ever remotely happened to me. Like him, I once got lost in a big city when I was about the same age, or a bit younger. I lived in Toronto where there is a huge Santa Claus parade just before Christmas. I had a job selling balloons along the parade route. When I ran out of balloons, I ducked into an alley to blow up some more. By the time I finished, the parade had passed, and the whole crowd was dispersing in different directions. It sounds impossible, but I lost the whole parade with its giant floats and clowns and everything. Then I lost myself trying to find the place where it was supposed to end—a downtown department store.

The rest of the story is imagined, and that’s one of the enjoyable things about writing. It’s like a big childhood game of pretending. What was it like to be a grave robber, or an old blind mudlark, or the captain of a sailing ship? Only a writer, I think, can be paid for thinking about that sort of thing.

Q. At what age did you know you wanted to be a writer? How long have you been a professional writer? Besides adventure, what other genres do you like to write in? When you write, do you set a schedule for yourself, or do you write when the story calls to you?

A. I don’t remember ever deciding to be a writer. In Grade 7, I was making little picture books for my younger brother, starring the stuffed duck that he had instead of a teddy bear. I wrote silly comics that were supposed to amuse my friends in school. When I started high school, I wanted to be a pilot, but when I finished I wanted to be a writer. I studied journalism in college, then worked for newspapers for the next 10 years. I was the editor of a small daily paper when I quit journalism to be a fish farmer, and to begin writing novels. But my first two published books were nonfiction, about my experiences sailing along the British Columbia coast in the summers. I hope that all my stories have some sort of sense of adventure, but I know what you mean about “besides adventure.” I like to write more thoughtful stories about characters growing and changing. I like it best if there’s a hint of mystery or magic about it.

Writing is my job, so I can’t sit around and wait for inspiration. I start work after breakfast, and keep going until mid-afternoon, when I take the dog for a walk. I write again after that, or take care of some of the business that goes along with writing.

Thanks to the following Teen Book Groups for participating!

Liberty Middle School Hungry Minds

Powell, Ohio

Elizabeth Public Library Teen Book Discussion Group

Elizabeth, New Jersey

Brook Haven School

Sebastopol, California

Flint Memorial Library Youth Advisory Board

North Reading, Massachusetts

Richmond Public Library

Richmond, British Columbia, Canada

Excerpt

I begin my adventure.

When she was six and I was eight, my little sister, Kitty, died. She fell from a bridge, into the Thames, and drowned before anyone could reach her. My mother was there when it happened. She heard a scream and turned to see my sister spinning through the air. She watched Kitty vanish into the eddies of brown water, and in that instant my mother’s mind unhinged.

She put on mourning clothes of the blackest black and hid herself from head to toe, like a beetle in a shell. As the sun went up, as the sun went down, she stood over Kitty’s grave. Her veils aflutter in the wind, her shawls drooping in the rain, she became a phantom of the churchyard, a figure feared by children. Even I, who had known her all my life, never ventured near the place when the yellow fogs of autumn came swirling round the headstones.

It was a day such as that, an autumn day, when my father had to drag her from my sister’s grave. The fog was thick and putrid, like a vile custard poured among the tombstones. From the iron gate at the street I couldn’t see as far as the church. But I saw the crosses and the marble angels, some distinct, some like shadows, and my father among them, as though battling with a demon. I heard my mother wailing.

Her boots were black, her bonnets black, and the rippling of her clothes made her look more like a beast than a person. She shrieked and fought against him, clinging to the headstone, clawing at the earth. When at last my father brought her through the gate, she was howling like a dog. In her hand was a fistful of dirt. She looked at it, and fainted dead away.

We lifted her into the cart, among the bundles and the chests that represented all our goods. The drayman climbed to his seat. He cracked his whip and swore at his horse, and off we started for Camden Town.

I walked beside my father as we passed our empty house and turned toward the bridge. By chance, the drayman chose the same route that Father took every morning on his useless treks to the Admiralty. I saw him look up at the house, then down at the ground, and we went along in silence. Only a few feet before me, the cart was no more than a gray shape. It seemed to be pulled by an invisible horse that snorted and wheezed as it clopped on the paving stones. My mother woke and sat keening on the cart. We were nearly at the river before my father spoke. “This is for her own good,” he said. “You know that, Tom.”

“Yes,” I said, though it wasn’t true. We were not leaving Surrey for my mother’s sake, but only to save the two pennies my father spent crossing the bridge every day. We were leaving because Mr. Goodfellow had driven us away, just as he had driven us from a larger house not a year before. I believed he would haunt us forever, chasing us from one shrinking home to the next, until he saw us out on the streets with the beggars and the blind. We were leaving Surrey because my father was a sailor without a ship.

He didn’t walk like a sailor anymore. He didn’t look like one, nor even smell like one, and I wouldn’t have believed he had ever been a sailor if it weren’t for the threadbare uniform he donned every morning, and for the bits of sailory knickknack that had once filled our house but now were nearly gone. In all my life I had watched him sailing out to sea only once, and then in a thing so woeful that it sank before he reached the Medway. That, too, had been Mr. Goodfellow’s doing; that had been the start of it.

When we reached the timber wharfs at the foot of the bridge I could feel the Thames close at hand. Foghorns hooted and moaned, and there came the thumping of a steamboat as it thrashed its way along the river. But I couldn’t smell the water; the stench of the fog hid even that.

We paid our toll and started over the bridge. Father walked at the very edge, his sleeve smearing the soot that had fallen on the rail. Horses and carriages appeared before us, and a cabriolet came rattling up from behind. I had to dodge around people, and step nimbly from a curricle’s path, but my father walked straight ahead with a mind only for the river below us. Ladies on the benches drew in their feet as he passed. One snatched up a little white dog. A man shouted, “Watch where you’re walking.” But Father just brushed by them all.

I imagined that he could somehow see the water, and all the life upon it. Sounds that drifted up to me as mere groans and puzzling splashes must, to him, have been visions of boatsmen and bargemen, of oars and sails at work. His head rose; his shoulders straightened for a moment.

I had no wish to know his world, though I had been born by the banks of the Thames, where the river met the sea. We’d left the village before I was two, at the wishes of my mother. The river had taken her father, and the sea had taken her brothers, and ever since my sister’s death she’d taught me to fear them both. I often thought–when I saw the Thames swirling by–that one or the other was waiting to take me too.