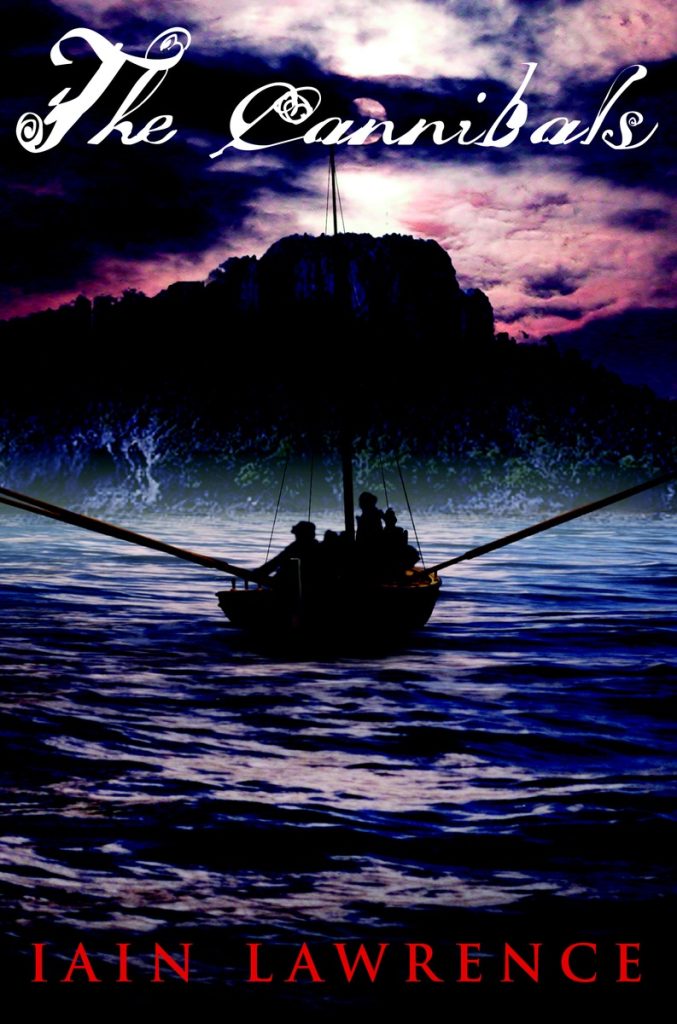

The Cannibals

Buy the Book: Amazon, Barnes & Noble, IndieBound, Indigo

Buy the Book: Amazon, Barnes & Noble, IndieBound, Indigo Published by: Random House

Pages: 240

ISBN13: 978-0440419334

Overview

As Tom Tin nears Australia, where he’s to serve a lengthy sentence for a murder he didn’t commit, he and his fellow convict, Midgely, plot their escape. No matter that the ship carrying them and the other juvenile criminals is captained by Tom’s father. Tom knows his father can’t help him clear his name and regain his freedom–not as long as Mr. Goodfellow, a man who wants the ruin of the Tin family, wields power back in London. So Tom and Midgely decide to go overboard! So do other boys who seize their chance at liberty–boys who aren’t so innocent, and who have it in for Tom. To make things worse, the islands in the Pacific look inviting, but Tom remembers his father’s warning that headhunters and cannibals lurk there! The boys go anyway. And as conflict among them mounts, as they encounter the very dangers Captain Tin spoke of, Tom must fight to keep himself and Midgely alive.

Praise & Awards

Selected as A Kirkus Reviews Editor’s Choice

“This book offers a Robert Louis Stevenson brand of excitement that will draw fans of exotic adventure tales. The book’s open ending will leave readers pondering the fates of the main characters and anticipating another installment of Tom’s adventures.”

— Publishers Weekly Read

“Fire-breathing monsters, headless corpses, gigantic snakes, a mysterious woman and islands full of cannibals make this high-spirited, old-fashioned adventure tale, complete with cliffhanger chapter endings, a treat.”

— Kirkus Reviews

“Lawrence keeps the reader on edge, ending chapters suspensfully and weaving seemingly disparate plot lines together; the conclusion is open enough to titillate readers with the promise of yet another high-spirited tale as the boys, chastened by many losses, stream past the islands toward home.”

— The Horn Book Magazine

Excerpt

Beyond the Cape of Storms

I came to know my father as we voyaged to Australia. At first he seemed a different man, his face sun burnt and bright, wrinkled round the eyes into a never-ending smile. Gone was his weariness, and years from his age. But he hadn’t really changed; I had only forgotten. Along with his sea clothes, he had donned his old self, becoming again the man I had known as a child.

I grew to love him as I had then, and saw my love returned, though not the way I wanted. Father could see that my time in the prison hulk had left me pale and thin, but not that I was stronger on the inside because of it. So he vowed to keep me safe, and cared so deeply for me that it proved our undoing in the end.

Five months out of England, we rounded the Cape of Good Hope. We stormed around it, in furious winds and tumbling cliffs of water. But I saw nothing but a patch of sky, a glimpse of sails through the ragged holes in an old tarpaulin.

A tangled fate had made my father my jailer, and now he was sailing me beyond the seas, in a ship that had been a slaver. He was the captain and I was a convict.

With sixty others I was penned below, in the dark and shuddering hull of the ship. The wind howled and tore at the tarpaulin that covered the hatch. Whole waves exploded through the grating, and for every drop of water that rained through the deck seams, a bucket’s load welled up through the timbers.

I found that I had not beaten my old fear of the sea. For nine days running I lay sick as a dog on my wooden berth, almost wishing for the ship to founder, yet terrified that it might. I clung to the ringbolts where the slaves had been chained, listening to the ocean batter at the planks. If it weren’t for Midgely I might have gone as mad as my poor mother. He was young and small, blinded in both eyes. But he stayed at my side, little Midge.

When the Cape was behind us, the weather cleared. The hatches were opened, and up we went to a sunlit morning.

My father was too kindhearted to be a jailer. Perhaps his spell in debtors’ prison had taught him the misery of confinement. He always gave us the run of the deck on fair-weather days. He’d let the crew indulge us with seafaring stories, and from time to time he had the fiddler play while we danced. Our prison wasn’t the ship, but the sea itself.

On this day we milled like cattle in the small space between the masts. Sailors were tightening the lashings on the piles of planks and timbers. Others worked high in the rigging, but it made me dizzy to turn up my head to watch them. Every sail was set, the brig pushing along below its towers of canvas. The air was hot. Water steamed from the deck and the sails and the rigging.

A sailor came for Midge and me. We were hurried off, up to the afterdeck and down to the cabins. My father was waiting below, standing by his broad windows that looked back where the ship had been. Our silvery wake stretched over the waves like the trail of a slug.

“Good morning, Captain Tin,” cried Midgely.

Father turned to greet us, a great smile on his face. “Good morning, William,” he said. He was the only one to call Midgely by his proper name. His hand fell upon my shoulder. “Are you bearing up, Tom?” he asked.

I nodded.

“You’ve weathered the storm, I see.”

“Oh, yes, sir,” said Midge. “It was a ripping storm, weren’t it?”

Father smiled. “Sit, boys,” he said, waving us toward his berth.

I took Midgely’s hand to guide him to our place. He could hardly see at all, and never when he went from sunshine into shadows. But he pulled away, and went straight to my father’s berth, dodging the table and dodging the chair. He’d learned the cabin well in the dozen visits we’d made. When I climbed beside him on the bed, it seemed the height of luxury to sit on a mattress again.

“What would you like?” asked Father. “Cheese? Bread and jam?” He always offered, and we always refused.

I went straight to the point. “Father, we have a plan,” I said.

He stood with his hands behind his back. The sea tilted and slashed across his windows, and he leaned from side to side against the roll of the ship. The motions made my stomach churn.

“We want to escape,” I said.

Father looked surprised. His mouth, for a moment, gaped open. Then a hearty laugh came out. “Escape?” he asked. His hand motioned toward the huge sea. “To where?”

Midgely answered. “To a place near Tetakari Island, sir.”

“Where the devil’s that?”

“South and east of Borneo,” said Midge. “But not as far as Java.”

My father frowned. He crossed the cabin to his table, then reached up to the rafters. His charts were stowed there, rolled into tubes, and he talked as he sorted through them. “I’ve never heard of such a place,” he said.

“Well, there’s an island near it what looks like an elephant,” said Midge. “The cliffs and the trees, they look like the elephant’s head. There’s a sandy beach, and coconuts and breadfruit. It was in the book. Ask Tom, sir. Ask him if it ain’t true.”

Father picked through his charts. “Well, books are travelers’ tales, you know. The writers fill them with nonsense.”

“But this one was wrote by a reverend, sir,” said Midge.

My father smiled back at him. Like every sailor on the brig, he adored little Midge. My friend might have been the ship’s cat for all the pats and treats that came his way. “Let’s have a look at your elephant island,” he said.