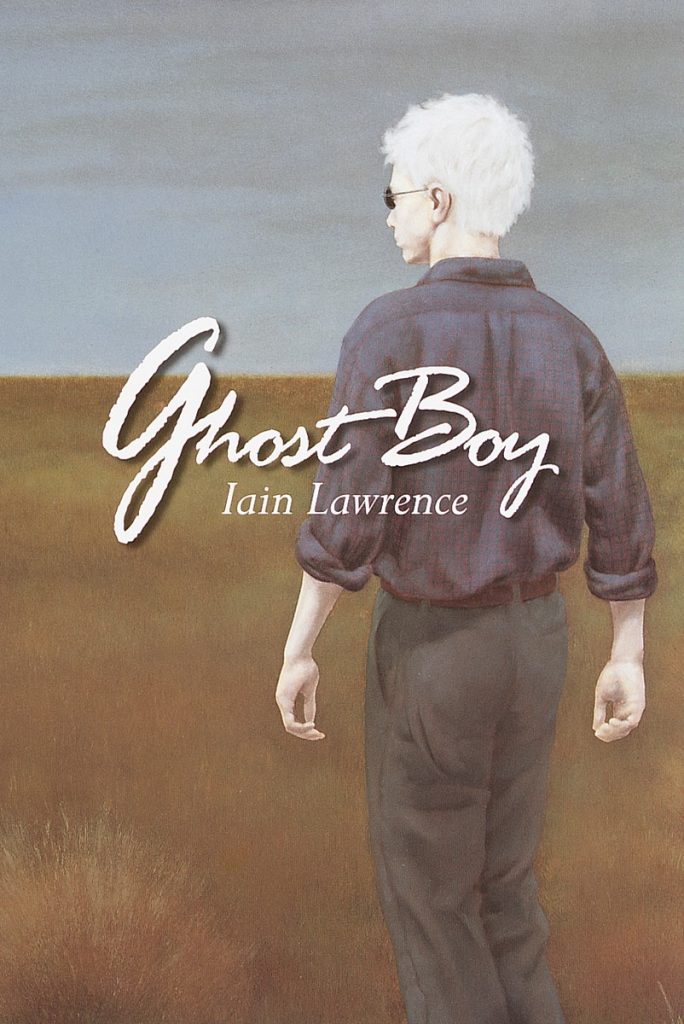

Ghost Boy

Buy the Book: Amazon, Barnes & Noble, IndieBound, Indigo

Buy the Book: Amazon, Barnes & Noble, IndieBound, Indigo Published by: Random House

Release Date: 02/11/2003

Pages: 352

ISBN13: 978-044041668

Overview

Harold Kline is an albino—an outcast. Folks stare and taunt, calling him Ghost Boy. It’s been that way for all of his 14 years. So when the circus comes to town, Harold runs off to join it. Full of colorful performers, the circus seems like the answer to Harold’s loneliness. He’s eager to meet the Cannibal King, a sideshow attraction who’s an albino, too. He’s touched that Princess Minikin and the Fossil Man, two other sideshow curiosities, embrace him like a son. He’s in love with Flip, the pretty and beguiling horse trainer, and awed by the allâ€-knowing Gypsy Magda. Most of all, Harold is proud of training the elephants, and of earning respect and a sense of normalcy. Even at the circus, though, two groups exist—the freaks, and everyone else. Harold straddles both groups. But fitting in comes at a price, and Harold must recognize the truth beneath what seems apparent before he can find a place to call home.

Guide

Praise & Awards

Selected, ALA Notable Book

Winner, ALA Best Book for Young Adults

Winner, A School Library Journal Best Book of the Year

Winner, Publishers Weekly Best Book

Selected, New York Public Library Book for the Teen Age

“The hero of this unusual and affecting novel about acceptance and belonging is an albino. Harold – people call him Ghost – runs away from home, from the taunts and teasing, from the meanspirited stepfather, and joins the circus passing through his prairie hometown, Liberty. Ghost makes friends with the Cannibal King, himself an albino, and becomes an elephant trainer. Eventually he is brave enough to go home.”

— New York Times Book Review Read

“Lawrence seamlessly shifts from the open sea (The Wreckers; The Smugglers) to landlubber territory with this tale of an albino boy who runs off to join the circus. Although the novel’s premise may be familiar, there is nothing conventional about the author’s portrayal of this taunted hero growing up in a post-WWII America. In lyrical prose, the narrative probes the isolation and alienation of 14-year-old Harold, better known as ’Ghost Boy…’ This poignant adventure invites readers to look beyond others’ outer appearances and into their souls.” *Starred Review*

— Publishers Weekly

“Lawrence’s outstanding coming-of-age novel features fascinating, fully rounded characters who drive the story forward while drawing readers in to think about perceptions vs. reality. The setting is wonderfully realized and captures the magic of the big top and the decidedly different world behind the scenes. This touching novel will speak especially to readers who consider themselves different, flawed, or misunderstood.”

— School Library Journal

“Lawrence has worked his magic with what could have been a commonplace story; his prose is near poetry, his characterizations, as usual, fascinating and unique. But it is the ache of Harold’s longing to be a part of something and the gift that these odd circus people offer that sets this coming-of-age road story apart from the average YA novel…Memorable in every way.” *Starred Review*

— Kirkus Reviews

Q&A

Q. What was the hardest part about writing this novel? What was the best part?

A. The hardest part was trying to imagine the world through Harold’s eyes. I spent a fair bit of time squinting at things, but never fully understood how things would actually appear to him. But apart from his vision, there was also the question of how he would imagine the world to be. Harold had lived all his life within a couple of miles of his house. He had never seen a television or a forest or a three-story building. But when he set off on his journey he had particular ideas of what all of those things would be like. And that was the question always in my mind: What would Harold make of this?

The best part, by far, was any scene involving Thunder Wakes Him. I developed a real fondness for the old Indian and his wandering existence.

Q. You are from Canada, yet you chose to set the story on the plains of America. What was the reason for this?

A. The story had to take place just after World War II, when the small-time traveling circus was fading into history, when sensitivities were bringing an end to the public display of “freaks” and “human oddities.” At that time, and still today, the towns of the Canadian West were smaller and farther apart than those south of the border. But more important to Ghost Boy is Harold’s journey to the West.

It’s an exploration for him, a small counterpart to the travels of Lewis and Clark and the settlers on the Oregon Trail. Like them, he goes west hoping to find a better life.

Q. Harold appears in and is the center of all that happens in the story. Why didn’t you have him tell the story in the first person?

A. I normally write at least one scene of a story in both third person and first, and then decide which I like better. With Ghost Boy, though, there was never a question. I didn’t feel capable of describing the world through Harold’s eyes and mind. An elephant, to him, would be a big, brown blur; a face might be unrecognizable. I imagine now that a story told in that way could be extremely powerful, every visual image mysterious, every sound sharp and clear. In retrospect, I probably should have tried to tell Ghost Boy that way, but I would probably still be struggling with the first few pages. As it is, I think the story already sometimes steps a bit too far from Harold’s point of view.

Q. You know more about the characters than you have told us. Can you give us more background?

A. I never develop detailed character sketches before starting a book. I’m more likely to write something brief, in the first person, that will give an idea of how the character sounds, and more interested in knowing his ambition than his past. So I really only have vague ideas myself about the background of the characters.

Thunder Wakes Him is just a middle-aged white man. He lived an ordinary life in an ordinary household, until he started performing his trick-riding act in the costume of a Plains Indian. His eccentric and romantic shift into a full-time portrayal of an Indian took place over time, until he now nearly panics when rain splotches his makeup. But it is recent enough that the circus people still know him as Bob. If Harold’s eyesight was better, and if he was a little less naïve, he would have seen through the makeup right away.

Samuel and Tina met at Hunter and Green’s and have been traveling together ever since. They intend to get married as soon as they have saved enough money to buy their little house. Tina is perfectly happy with her lot in life; she has never wished to be anything else than she is. Samuel, though, is often bitter and angry at the world in general. Abandoned by his parents, sold into a type of circus slavery, he carries on for Tina’s sake alone, and will likely quit the circus before another summer’s over. Mr. Green has been looking for ways to make money ever since he was a child. He formed Hunter and Green’s only a few years before the story began. He sees it only as a business and lacks the ambition and the imagination to turn it into anything better.

Flip grew up in circuses. Her parents were stars in a much larger European circus before coming to America to escape the looming war in Europe.

Q. Did you consider a different climax to the novel–another event other than Tina’s death that would allow Harold to take what he’s learned and return home?

A. The story was only roughly plotted, but I knew from the first word that Tina would die. I nearly changed my mind when I reached that point in the story. She had become so real then that I could hear her voice in my mind and see how she walked and stood and gestured. I actually cried as I wrote the scene, and in the days that followed felt terribly guilty. But Harold brings everything on himself: He largely ignores the warnings of the Gypsy Magda; he doesn’t listen to Flip when she tells him he’s spoiling the elephants. The discovery that the elephants make him powerful, and his love of that power, lead inexorably to Tina’s death. The elephant is only protecting him from an imagined threat.

In the original plot outline, Harold found his brother. He saw him in the bleachers as he rode the elephants round the circus ring. Apart from the unlikelihood of that–the faces would all be blurs to Harold–it didn’t seem to help the story. Harold would naturally go home with his brother, ending his journey right then. It wasn’t much of a resolution.

Q. Many of the themes you explore in the book appear throughout literature. What books influenced you in the writing of Ghost Boy?

A. It was the idea of elephants playing baseball that started Ghost Boy. I was well into the story when I started thinking about Toby Tyler: or, Ten Weeks with a Circus, a book I loved as a child, and the basis for a Disney movie I remembered enjoying very much. It was a bit of a shock when I saw it again, as I discovered that I was basically rewriting this half-forgotten story. I threw out all that I’d done and started over, shaping the story around Harold instead of the elephants. I looked for novels about people with albinism, but found very few. The only one I was familiar with was Erskine Caldwell’s God’s Little Acre, though just from the movie version. In Ghost Boy, Wicks, the circus cook, imagines that all albinos can sniff out gold and dowse for it with forked sticks. I hoped the reader would conclude that Wicks had formed this opinion by reading Caldwell’s book. A friend in Prince Rupert [British Columbia] read my developing story and pointed out that Harold was quite close to the classical hero, that in searching for the Cannibal King he was off on an almost heroic quest. My friend steered me toward Joseph Campbell’s The Hero with a Thousand Faces, but while I delved into this study of myths and heroes, it’s hard to say how much influence

it really had.

Unfortunately, I don’t keep good records of my research material. I read many books about circuses, looking specifically for first-person accounts from days long

enough past to include memories of freak shows.

Q. How much of the story did you mean for readers to take literally and how much for them to take on another level–metaphor, fantasy?

A. Ghost Boy is a fairly simple story meant to be taken pretty much as the truth, though parts of it definitely stretch the bounds of credulity. The reader, though, is meant to wonder for a while if the old Indian really does exist when he offers to take Harold off on his journey. It’s not until the very ending, when the children of Liberty acknowledge that Harold has been gone for some time, that there’s really no doubt that the entire story isn’t taking place within Harold’s mind as he sits in the empty field near Liberty.

Q. In the late 1940s, the circus was often the only place where people with gross physical deformities could find work. Such sideshow performers were exhibits and commonly called freaks. In today’s more sensitive times such language and treatment have been expunged from popular culture. Why did you choose to use such blatant language? What did you anticipate your teen readers’ reactions would be to such language in print? What about the reactions of adult readers?

A. To be true to the period, Samuel and Tina and even the Cannibal King had to be referred to as freaks. I understood that the word, without even quotation marks around it, would appear insensitive or jarring to some people, but I never doubted that it was the right thing to do.

Nearly every character in Ghost Boy turns out to be a bit of a paradox. The monstrous ones are really nice people inside, while the nice people act in monstrous ways. Though that was a deliberate choice, I didn’t intend the book to be a lesson in how to judge, or not judge, people. That was something for Harold to learn. I suppose, though, that it is a reflection of how I see the world, as I believe that no one can ever truly know anyone else. Quite possibly, you can never really know yourself.

There are other sensitivities. Harold is referred to as “that poor albino boy,” not as “that poor boy with albinism.” Thunder Wakes Him is “the old Indian” instead of “the old Native American.” But to force the politically correct terms into the characters’ mouths would have sounded absurd. Ghost Boy was supposed to create a believable world for a boy in the 1940s, and I’ll be very disappointed if it’s criticized for its use of cruel-sounding terms.

Q. On second and even third readings of Ghost Boy, the richness of the language, the themes, and the characters reveal new levels of meaning to the reader. Does this happen to you as the writer as well? Can you give specific examples?

A. The original version of Ghost Boy contained many more references to race and skin color. Thunder Wakes Him, especially, went on at great length about the meaning of being white. Ghost Boy’s editor, Françoise Bui, encouraged me to take most of it out, and I’m very glad that she did. What is left comes naturally from the characters as they discuss their particular worries and hopes.

I think this is the time when most of those changes were made–the ones that were at once the smallest and the biggest. Françoise would mark a sentence as being unclear or a passage as being heavy-handed, and the rewriting would bring out the intended meaning.

As an aside, you might be interested to know that I’m just old enough to remember what was probably the very last of the traveling freak shows. When I was ten or eleven, I went to the Calgary Stampede with my brother and two cousins. We had just enough money to last the whole day if we were careful where every penny went.

I remember standing outside a booth of painted canvas, listening to the talker describe the creature inside and debating whether it was worth spending the dime to get inside. We sent a cousin as a scout, and she paid her dime and climbed up to a little platform where she had to peer down behind a screen. I can’t remember what we hoped to see, but I can still see her standing there, shouting at us in a voice loud enough to carry halfway down the midway, “This is a gyp! He’s just sitting there doing nothing.” To this day, I’m glad every time I think of it that I didn’t pay my dime and see that poor soul inside.

Excerpt

Chapter 1

It was the hottest day of the year. Only the Ghost was out in the sun, only the Ghost and his dog. They shuffled down Liberty’s main street with puffs of dust swirling at their feet, as though the earth was so hot that it smoldered.

It wasn’t yet noon, and already a hundred degrees. But the Ghost wore his helmet of leather and fur, a pilot’s helmet from a war that was two years over. It touched his eyebrows and covered his ears; the straps dangled and swayed at his neck.

He was a thin boy, white as chalk, a plaster boy dressed in baggy clothes. He wore little round spectacles with black lenses that looked like painted coins on his eyes. And he stared through them at a world that was always blurred, that sometimes jittered across the darkened glass. From the soles of his feet to the top of his head, his skin was like rich white chocolate, without a freckle anywhere. Even his eyes were such a pale blue that they were almost clear, like raindrops or quivering dew.

He glanced up for only a moment. Already there was a scrawl of smoke to the west, creeping across the prairie. But the Ghost didn’t hurry; he never did. He hadn’t missed a single train in more than a hundred Saturdays.

He turned the corner at the drugstore, his honey-colored dog behind him. They went down to the railway tracks and the little station that once had been a sparkling red but now was measled by the sun. At three minutes to noon he sat on the bench on the empty platform, and the dog crawled into the shadows below it.

The Ghost put down his stick and his jar, then dabbed at the sweat that trickled from the rim of his helmet. The top of it was black with sweat, in a circle like a skullcap.

The scrawl of smoke came closer. It turned to creamy puffs. The train whistled at Batsford’s field, where it started around the long bend toward Liberty and on to the Rattlesnake. The Ghost lifted his head, and his thin pale lips were set in a line that was neither a frown nor a smile.

“It’s going to stop,” he told his dog. “You bet it will.”

Huge and black, pistons hissing steam, the engine came leaning into the curve. It pulled a mail car and a single coach in a breathy thunder, a shriek of wheels. It rattled the windows in the clapboard station, shedding dust from the planks. The bench jiggled on metal legs.

“I know it’s going to stop,” said the Ghost.

But it didn’t. The train roared past him in a blast of steam, in a hot whirl of wind that lashed the helmet straps against his cheeks. And on this Saturday in July, as he had every other Saturday that he could possibly remember, Harold the Ghost blinked down the track and sighed the saddest little breath that anyone might ever hear. Then he picked up his stick and his jar and struck off for the Rattlesnake River.

The stick was his fishing pole, and he carried it over his shoulder. A string looped down behind him, with a wooden bobber swinging at his knees. The old dog came out from the shade and followed him so closely that the bobber whacked her head with a hollow little thunk. But the dog didn’t seem to mind; she would put up with anything to be near her master.

They climbed back to Main Street and trudged to the east, past false-fronted buildings coated with dust. The windows were blackboards for children’s graffiti, covered with Kilroy faces and crooked hearts scribbled with names: Bobby Loves Betty; Betty Loves George; No One Loves Harold. And across the wide front window of May’s Cafe was a poem in slanting lines:

He’s ugly and stupid He’s dumb as a post He’s a freak and a geek He’s Harold the Ghost.

In the shade below the window sat a woman on a chair with spindly legs, beside a half-blind old man with spindly legs sitting in a rocker. Harold glanced at them and heard the woman’s voice from clear across the street. “There he goes,” she said. “I never seen a sadder sight.”

He couldn’t hear the old man’s question, only the woman’s answer. “Why, that poor albino boy.”

The man mumbled; she clucked like a goose. “Land’s sakes! He’s going to the river, of course. Down where the Baptists go. Where they dunk themselves in the swimming hole.”

His head down, his boots scuffing, Harold passed from the town to the prairie. The buildings shrank behind him until they were just a brown-and-silver heap. And in the huge flatness of the land he was a speck of a boy with a speck of a dog behind him. He walked so slowly that a tumbleweed overtook him, though the day was nearly calm. In an hour he’d reached the Rattlesnake.

In truth it was no more of a river than Liberty was a city. The Rattlesnake didn’t flow across the prairie; it crawled. It went like an ancient dog on a winding path, keeping to the shade when it could. But it was the only river that Harold Kline had ever seen, and he thought it rather grand. He splashed his way along the stream, a quarter mile down the river, until he reached his favorite spot, where the banks were smooth and grassy. Then he sat, and the dog lay beside him. He put a worm on his hook and cast out the bobber. It plunged in, popped out, tilted and straightened, like a little diver who’d found the river too cold. A pair of water striders dashed over to have a look at it, and dashed away again.

The dog was asleep in an instant. She hadn’t run more than a yard in more than a year, but she dreamed about running now, her legs twitching.

“Where are you off to?” asked Harold the Ghost. His voice was soft as smoke. “You’re off to Oregon, I bet. You’re running through the forests, aren’t you? You’re running where it’s cool and shady, you poor old thing.” He looked up at the sun, a hot white smudge in his glasses.

The dog went everywhere Harold did. It seemed only natural to him that she would dream of the places he dreamed about.